By: James Bascom

Source: Link

Travel back in your mind 1,500 years to a charming port city on the English Channel in northern France. It is the year 636 A.D. and a small boat without sails, oars, or sailors floats into the harbor of Boulogne-sur-Mer.

As the townspeople gather around it, they discover that the boat contains an innocuous treasure: a wooden statue of Our Lady holding the Child Jesus in her left hand. She has an air of divine majesty, yet is calm and maternal. Our Lady’s statue is solemnly carried into the chapel and the newly christened shrine of Notre Dame de Boulogne became one of the most well-known and visited shrines in Christendom. Her feast day is February 20, and is celebrated locally in Boulogne on October 22. Medieval chroniclers wrote about the many miracles of Our Lady of Boulogne. A chronicle of the life of the holy King of France, Saint Louis IX, includes several references to the miraculous cures obtained through the intercession of Our Lady of Boulogne. She was especially powerful towards sailors and expectant mothers.

England Invades

In 1544, disaster came to Boulogne-sur-Mer. Henry VIII, King of England, declared war on France and sent a fleet with 47,000 troops across the Channel. One of the first cities he attacked was Boulogne, laying siege to it on July 18. Boulogne, although a walled city with very strong defenses, was manned by only 2,000 soldiers. The city surrendered on September 14, 1544. The invading Protestant army sacked the city. Statues, altars, relics of saints and other sacred objects were hacked to pieces and burned in the streets in an orgy of hatred for the Catholic Faith. Worst of all, the statue of Our Lady of Boulogne was dragged out of the church, mocked and insulted and taken back to England as a trophy of victory. They transformed Our Lady’s medieval shrine into an armory. The English finally surrendered Boulogne on April 25, 1550, and shortly afterwards returned the statue of Our Lady. The church and city were rebuilt and restored over the following decades and Our Lady’s shrine reacquired much of its original splendor.

Huguenots Attack

The same Revolutionary virus that had infected Europe was preparing bloody rebellion and religious civil war in France with the Huguenots, the French Protestant sect. During the night of October 11, 1567, hundreds of Huguenot soldiers secretly broke into the church of Our Lady of Boulogne. They wrecked the church and tore out the miraculous statue. Tying a rope around her neck, they dragged her through the muddy streets until they reached the main gate of the old town. There they mocked and blasphemed her. But when they tried to chop Our Lady into pieces, a miraculous force protected her. They hit her over and over again with swords and hammers, but the statue, as if made of steel, suffered no damage. The miracle infuriated the Protestants even more, and they threw the statue into a great bonfire. Again, Our Lady was miraculously preserved intact amidst the flames. The Huguenots took the statue out of the city and they threw her down a well. By the following spring, order was restored to the port city. A local Catholic woman, knowing the whereabouts of the miraculous statue, secretly retrieved it and took it to her house. On September 26, 1607, to the acclamations of large crowds of faithful, Our Lady solemnly reentered Boulogne.

Devastation of the French Revolution

The French Revolution began in 1789 with tragic consequences for France and Our Lady of Boulogne. On November 10, 1793, after the Revolutionaries in Boulogne finished celebrating in a former church the so-called “Feast of the goddess of Reason,” they began an orgy of destruction. Full of hate for the Catholic Faith, they piled numerous statues, paintings, vestments, and relics in the city square and destroyed everything in a giant bonfire. A mob of thugs armed with picks and screaming the Marseillaise dragged Our Lady of Boulogne to the main square. The sans-culottes put a red Phrygian cap on Our Lady’s head, symbol of the French Revolution, and began to mock and blaspheme her. When they tired of this, they burned her in a great bonfire, dancing like savages in celebration for the victory of “reason” over “superstition.”

Not satisfied with the destruction of the miraculous statue, in 1798 the revolutionary government completely demolished the shrine. Devotion to Our Lady of Boulogne, who for more than eleven centuries had served as a symbol of the mutual love between the French people and the Mother of God, came to an end. Or did it? Did Our Lady abandon the France that had abandoned her? Or, seeing her children do penance and return to the true Faith, would she make a Grand Return just as she did after the previous disasters, first under the English and then under the Huguenots?

A New Statue, a New Shrine

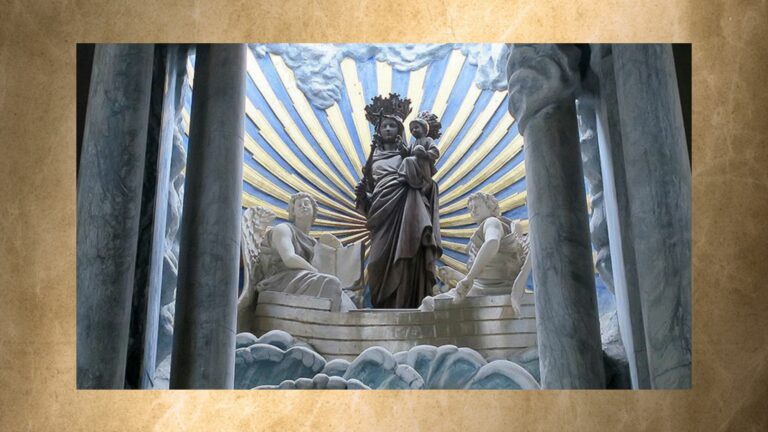

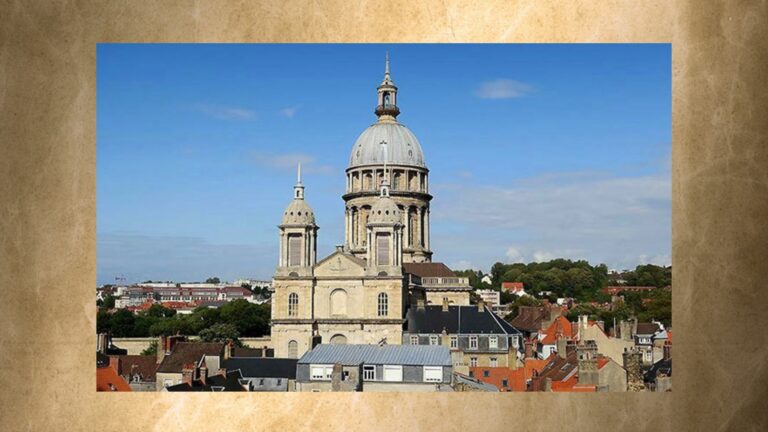

Shortly after the end of the French Revolution, the Catholics of Boulogne decided to make a copy of the original statue of Our Lady of Boulogne from memory, and the devotion to Our Lady of Boulogne began once again. Father Benoît-Agathon Haffreingue, a priest from Boulogne-sur-Mer, decided to rebuild the ruined church. On May 1, 1827, he laid the first stone of the new shrine of Our Lady of Boulogne, which was completed thirty-nine years later on August 24, 1866. Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims poured into Boulogne each year. Devotion to Our Lady of Boulogne surpassed what it had been even before the French Revolution. France and Europe had much more suffering ahead of them. The Franco-Prussian war and the First World War utterly devastated France. It was during the Second World War, however, that Our Lady of Boulogne worked her greatest miracle: the Grand Retour or the “Grand Return.”

Origins of the Grand Return

In the summer of 1938, Boulogne hosted a Marian Congress. To prepare the faithful for this national event, two priests decided to make four copies of the original statue of Our Lady of Boulogne and take them on a great tour of the towns and parishes of the diocese. Christened the “Fiery Path,” it was a success far exceeding expectations. In ten weeks the four statues covered more than 1,500 miles and made 466 stops at parishes. After the close of the Marian Congress, some clergy led by Father Gabriel Ranson, a Jesuit, decided to continue this “Fiery Path” of Our Lady around France until the next Congress, to be held in the summer of 1942 in Le Puy, in southern France. In the fall of 1939 and the spring of 1940, he and a handful of young laymen took Our Lady of Boulogne to northeastern France where they visited many parishes, as well as battlefields from the First World War. When Nazi Germany invaded France on May 10, 1940, Our Lady’s statue was in Reims. The war immediately stopped her travels and they hid her in the Trappist monastery for safekeeping, where she stayed for two years. However, Catholics clamored for Our Lady of Boulogne to join the Congress as originally planned, so in the summer of 1942 she continued her journey across France in the direction of Le Puy. After a very successful Congress, Our Lady of Boulogne continued her tour of France to Lourdes. She arrived there on September 7, 1942, eve of the Nativity of Our Lady, greeted by a massive crowd of pilgrims. With her triumphal entry into Lourdes, it seemed that Our Lady’s great tour of France would come to a close. Precisely at this moment, Pope Pius XII made a direct appeal to the Mother of God. On December 8, 1942, feast of the Immaculate Conception, the Supreme Pontiff consecrated the human race to the Immaculate Heart of Mary. The following year, on March 28, 1943, the French bishops solemnly renewed this consecration. This day was also the beginning of what came to be known as the Grand Return of Our Lady of Boulogne.

The Grand Return Begins

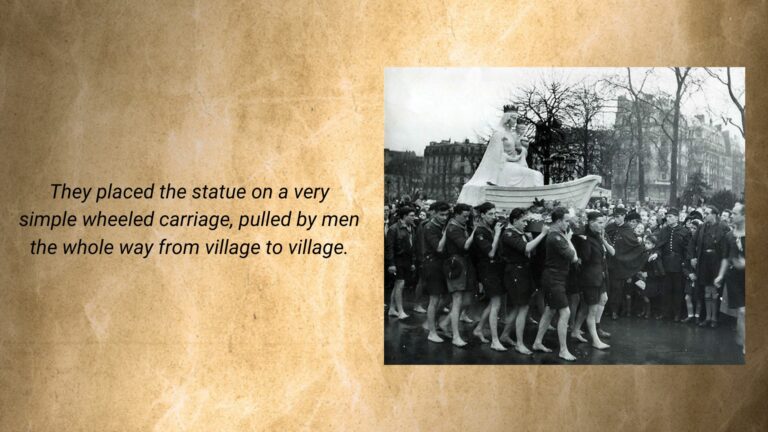

The bishop of Tarbes, where Lourdes is located, had the idea of sending the statue of Our Lady of Boulogne to each of the parishes of his diocese in pilgrimage. During each stop, the faithful would renew the consecration to the Immaculate Heart of Mary. After passing through his diocese and others across France, Our Lady would make her final return to Boulogne, hence the name “Grand Return.” The response was so great that the organizers decided to send all four copies of Our Lady of Boulogne around France on four different itineraries. With the letter of approval from Pope Pius XII in May, the four began their great tour of France, which would continue without stopping for five years straight. Each statue traveled with a group of about a dozen or so young men, all volunteers, led by two or three priests. They placed the statue on a very simple wheeled carriage, pulled by men the whole way from village to village. These men and the whole crowd often processed barefoot in a spirit of penance. When Our Lady arrived at the local parish, an honor guard would carry her into the church. The priest would preach a sermon on Our Lady of Boulogne and the meaning of the Grand Return, and they would hear confessions. Then the all-night vigil would begin, with villagers taking one or often many hours during the night. At midnight, Mass would begin. Each person received a copy of the Consecration to the Immaculate Heart of Mary of Pope Pius XII. The whole congregation would pray the consecration aloud and each one would sign it and place it at the feet of Our Lady, along with other written intentions.

With World War II underway, the intentions were often simple requests for the safe return of a father, husband, brother, or son from a prison camp or working as a forced laborer in Germany. Many asked for the conversion of a family member. Everyone asked Our Lady to save France. The all-night vigil continued until the following morning. In the morning, the priest celebrated a Mass of farewell. A large crowd of villagers gathered once again to escort the Blessed Virgin all the way to the next town, where a crowd of faithful had already gathered, and the sequence began again.

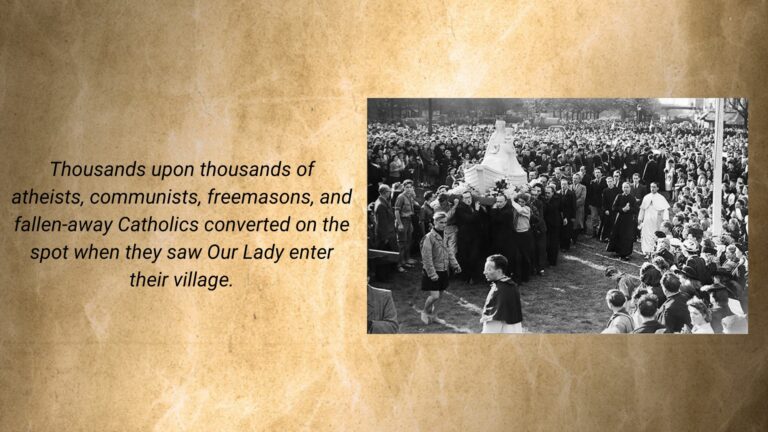

Conversions, Penance, Graces

Most remarkable about the Grand Return was the unprecedented avalanche of graces, especially of conversions and penance. Thousands upon thousands of atheists, communists, freemasons, and fallen-away Catholics converted on the spot when they saw Our Lady enter their village. One bishop described the effect on the faithful: “The passing of Our Lady in my diocese is the most extraordinary contemporary religious event of our times, and the most significant. Crowds of people rose up, motivated and enthusiastic. In fact, the confessionals and communion rails were besieged during the holy vigils, while the recitation of the mysteries of the rosary kept the faithful praying in the churches. In some parishes, there were tremendous conversions like never seen before on the missions.”

Parish priests also testified to the effect of the Grand Return. “I was a bit uneasy about the welcome that my very indifferent parish would give to Our Lady. People around me said that the welcome would be mediocre…Three kilometers from [our village of] Nantiat, we see the delegation of this parish, my parish. And I was moved to tears when I saw how big it was: men and young men, women; the whole crowd did not hesitate to kneel upon the wet ground, with arms in the form of a cross, to greet our illustrious Visitor…Truly the Holy Virgin has sent a breath of grace on this not very religious community.”

Another prelate testified: “Last Saturday, at around 2 pm, the Virgin arrived at [our] parish of Basville. For centuries no doubt, ever since the beginning of the world maybe, no king, no queen, no princess so royal or so powerful had ever visited us. Truly, this evening was at the least a return to Christianity, a general conversion, a call of my people to Our Mother and Queen…Yes, I think that if the Bishops send us a Virgin every year, in ten years the people of France will convert to Jesus Christ through Mary.”

One observer wrote the following: “It is like the atmosphere at Lourdes. We would dare say that it is stronger than Lourdes in a certain sense. The pilgrim of Lourdes is transplanted out of his element into an ambience that is so impregnated with the supernatural that nothing appears difficult to him, neither the rosary in his hand nor prayer with the arms in the form of a cross, nor to kneel in the dirt. These gestures of faith, Our Lady of Boulogne makes us do them where we live, in our street, under the attentive gazes of our neighbors, of people whom we know. We are no longer worried about what they think, and they don’t dare laugh or criticize.”

When the Grand Return arrived in Marseille, she passed through a neighborhood known for its support for communism. As she passed by a bar in which some communists were gathering for a meeting, several came out to investigate the commotion. The passing of the white Virgin had such an effect on them that they converted on the spot and joined the procession. In some cities such as Verdun, Bauvais, and Reims associations of so-called “freethinkers” tried to organize counterdemonstrations against the scheduled appearances of Our Lady of Boulogne. In each case the plan backfired. So many people came out for Our Lady and so few “free-thinkers” showed up that it made them look ridiculous. In Reims, after a big propaganda campaign, the “freethinkers” were only able to gather 12 people against 35,000 who turned out for Our Lady.

Return to God, to the Church, to the Medieval Faith

A Benedictine monk who had a role in the Grand Return, Father Jean-Marie Beaurin, published a book in 1945 titled The Arc of Our Alliance. He described the Grand Return as a prophetic movement and compared what was happening to the French nation with the apostasy, suffering, and conversion of the Jews of the Old Testament. After the abomination of desolation, the ingratitude, the declarations of the Popes and the apparitions of Our Lady, and finally the wrath of God, France was returning to the Faith of Clovis, Saint Remigius, Saint Louis, and Saint Joan of Arc. This rebirth of the Faith that followed the Grand Return was not a Catholicism impregnated with the modern spirit. Father Beaurin described the spirit of the Grand Return as a rebirth of the medieval Faith and the spirit of the Crusades. The Bishop Paul Rémond of Nice affirmed this about the Grand Return: “It is not a triumphal cortege, comprised of processions, or of grandiose manifestations… It is much greater than that: the Grand Return is a testimony of filial affection and thanksgiving to our benefactress in Heaven. It is a passing mission, a conquering crusade.”

Shortly after World War II ended, the Grand Return began to spread across the world, to Italy, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Canada, and even as far away as Ceylon, Madagascar, and China. In Italy, hundreds of cities were visited by pilgrim statues of Our Lady in the same manner as the French Grand Return. On May 11, 1947, more than 100,000 people gathered in Milan to welcome the traveling Madonna with unprecedented devotion and Catholic fervor.

End of the Grand Return

In short, the Grand Return was both a mission and a crusade. It represented the beginning of a rebirth of the French Medieval Catholicism with its crusading spirit and the rejection of the French Revolution and all its errors. Everything about the Grand Return seemed to indicate that it was the means that Divine Providence chose to re-Christianize France, and through the first-born daughter of the Church, the whole world. Tragically, this never happened. On August 29, 1948, the four traveling statues converged at the shrine of Boulogne-sur-Mer for the last time, effectively ending the Grand Return. Why did this movement—the biggest public manifestation of piety in history—end so prematurely? Partially, because the Catholic faithful did not correspond to the grace of the Grand Return as they should have. Millions of Frenchmen returned to the Faith, but millions of others did not. In addition, the majority of French bishops and lower clergy did not receive and promote the Grand Return as they should have. Many were believers in false “ecumenism” and disliked processions or public acts of piety. Others supported the Modernist, progressivist, and even socialist tendencies found in Catholic Action, Jeunesse ouvrière chrétienne (Young Christian Workers), the Liturgical Movement, and the Worker Priest Movement and therefore did not look kindly on traditional Catholic spirituality in general, much less a Marian crusade like the Grand Return. Cardinal Achille Liénart of Lille (whose open support for socialist causes earned him the nickname “the red bishop”) summarized the general attitude of a large portion of the clergy. He did not ban the Grand Return outright from his diocese but wrote a cold letter to the organizers: “I think that this long voyage which began in Lourdes in 1943 and which, no doubt, has done great good, should not continue indefinitely. In order to protect its effectiveness and vigor, you should not transform it into a permanent institution. I wish therefore the return of this statue without delay to Boulogne from where she came.”

Why We Hope for a Future “Grand Return”

But that is not the end of the story. More than anything, the story of Our Lady of the Grand Return should give us boundless hope for the future. Professor Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira learned about the Grand Return during his trip to Europe in 1952. As a slave of Our Lady according to the method of Saint Louis de Montfort, he was keenly interested in the story of Our Lady of the Grand Return. It was obvious that the world did not convert even after the horrors of the Second World War. As a devotee of Our Lady of Fatima, he was convinced that another even more terrible chastisement would come. Drawing on the words of Our Lady of Fatima and the writings of Saint Louis de Montfort, Professor Plinio hypothesized that this chastisement would be characterized by confusion in the Church and a terrible persecution of Catholics. After suffering this terrible chastisement, an “era of peace” would begin as Our Lady of Fatima predicted. This “Reign of Mary” cannot come without many, many conversions. Total conversions, in the same line as Saint Paul. Conversions not just of individuals, but of whole nations. We need a very special grace from Our Lady, one that would be analogous to that of Pentecost for the Apostles. Just as it was impossible for the Apostles to go out and convert all nations without the coming of the Holy Ghost at Pentecost, we will not have the strength to build the Reign of Mary without a very special grace. And it will be completely unmerited, just as Pentecost was unmerited by the Apostles, who had fled Our Lord during the Passion. Saint Louis de Montfort alludes to this grace of conversion in his writing. Professor Plinio developed a whole theory about it and named this future grace the Grand Return. More than anything, the Grand Return is our great hope for the future. We have hope that Our Lady will pardon us, cure us, convert the world, and inaugurate the Reign of Her Immaculate Heart. Most important of all, we must all stay at our post, fighting with all we have, until that D-Day of Our Lady comes.